Google DeepMind’s latest release, WeatherNext 2, has elevated the task of checking the weather to an hourly and real-time level.

It operates eight times faster than its predecessor and has improved its resolution to an hourly basis. This means that instead of traditional forecasts like “It will rain tomorrow afternoon,” it can provide details such as “There will be light rain from 2 to 3 PM tomorrow, with the rain intensifying from 3 to 4 PM and gradually stopping from 5 to 6 PM.”

Interestingly, it doesn’t just offer a single version of the forecast but can generate dozens or even hundreds of possible weather evolution scenarios from the same input.

Tasks that would take traditional supercomputers several hours to complete can be finished by WeatherNext 2 in just one minute using a single TPU.

As a result, 99.9% of its forecast variables and timeframes surpass those of the previous generation WeatherNext. It can also detect the potential impact range of extreme weather events like high temperatures and heavy rainfall much earlier.

So why does weather forecasting need to be so detailed?

Let the Model Transform into a Miniature Earth

Firstly, in reality, many industries are closely tied to the weather.

Energy systems rely on it to coordinate loads; urban management uses it to arrange manpower; agriculture depends on it to set the pace; and logistics and flights constantly monitor it to make decisions.

Moreover, the atmospheric system can be viewed as a vast chaotic machine where any minor disturbance may influence cloud movements or rainfall ranges days later.

The traditional approach involves running numerous predictions with different initial conditions and then identifying the most probable trends from thousands of results. However, this method is extremely computationally intensive.

The key to making WeatherNext 2 both fast and accurate lies in Google DeepMind’s newly proposed Functional Generative Networks (FGN).

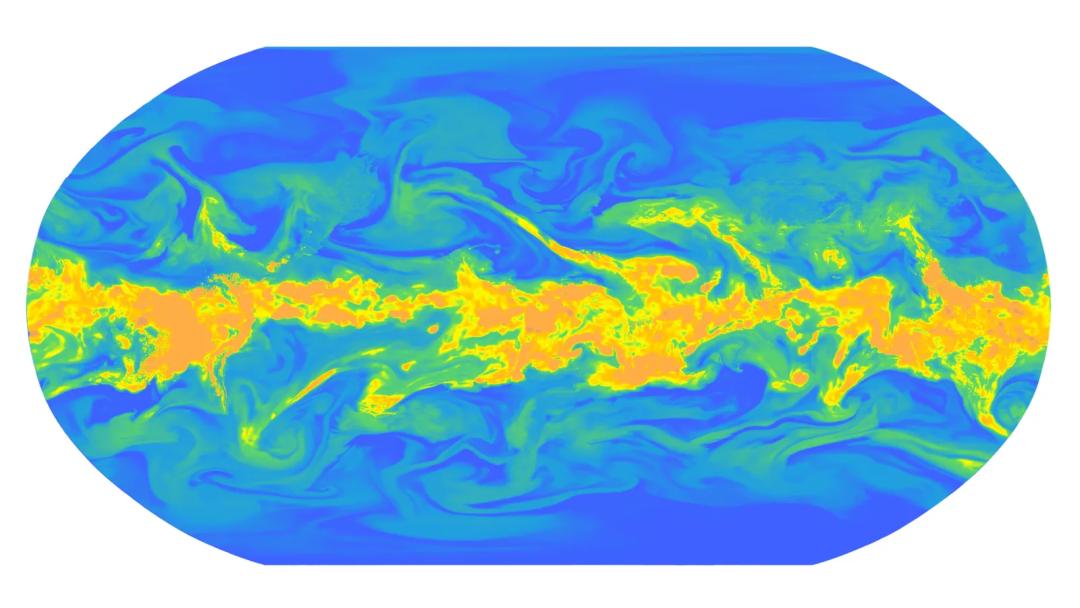

The FGN approach is quite different. Instead of stacking more physical equations or simulating the weather itself, it transforms the model into a changing miniature Earth by adding slight but globally consistent random perturbations to the model’s core.

More specifically, FGN inputs a 32-dimensional small random vector, or 32 random numbers, during each prediction. This random vector passes through all layers of the model, controlling its internal states and allowing the model to naturally generate a complete set of future weather fields.

Each set of random numbers represents one possible future, and changing to another set of random numbers yields a different future.